Plants have resources, and bacteria want them. Plants have gates on their leaves to keep the thieves out. But a nasty bug called Salmonella has figured out how to trick plants into opening up their safety gates so it can sneak in and live happily inside.

When people eat those contaminated leaves, they can get sick, sometimes severely.

© Trina Kleist/UC DavisDoctoral student Zachariah Jaramillo in the lab of UC Davis Professor Maeli Melotto. He is preparing material taken from a lettuce leaf to view a magnified image, which he'll use to measure the response of the plant to invading Salmonella bacteria.

© Trina Kleist/UC DavisDoctoral student Zachariah Jaramillo in the lab of UC Davis Professor Maeli Melotto. He is preparing material taken from a lettuce leaf to view a magnified image, which he'll use to measure the response of the plant to invading Salmonella bacteria.

Now, researchers at UC Davis have figured out how Salmonella does its dirty work: Plants close their safety gates when they detect the invader. But the bug somehow induces the production of a chemical hormone called auxin, which gives a kind of false "all-clear" signal that causes the poor plant to open its gates and let the squatter in.

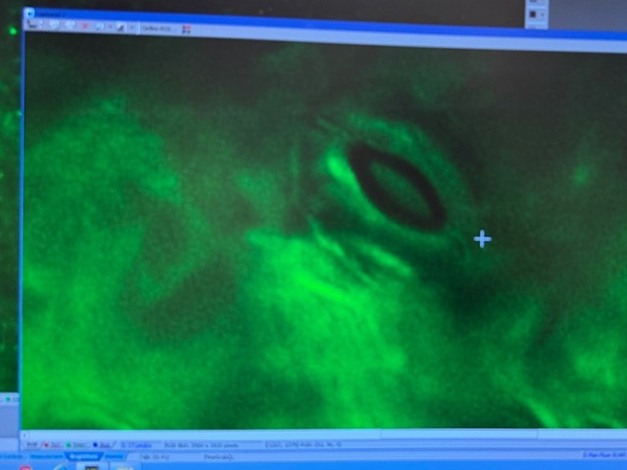

© Trina Kleist/UC DavisThis large, dark, oval shape is an open pore, or stomate, on the surface of a lettuce leaf. Grad student Zachariah Jaramillo put a tiny bit of lettuce leaf under a special microscope, then pulled up the image onto a computer screen

© Trina Kleist/UC DavisThis large, dark, oval shape is an open pore, or stomate, on the surface of a lettuce leaf. Grad student Zachariah Jaramillo put a tiny bit of lettuce leaf under a special microscope, then pulled up the image onto a computer screen

The discovery by a team led by Maeli Melotto, a professor in the Department of Plant Sciences, is good news for efforts to breed lettuce and other leafy greens to resist sneaky microbes. Their research was featured on the issue cover of the prestigious open-access journal PLOS Pathogens. The lead author is Brianna Fochs, who was a Ph.D. student in Melotto's lab and has since graduated.

Most of their research was done in the model plant Arabidopsis, but the mechanism is similar for lettuce, spinach, basil and other crops. Infected greens are the source of more than 9 percent of foodborne illnesses across the country, sickening an estimated 2.3 million people and costing up to $5.3 billion every year.

"We are now a step closer to translating this knowledge to leafy greens and start breeding for safer crops," Melotto said. "But additional research is needed to solve the problem."

The team included grad student Zachariah Jaramillo, who took the winning cover photo. Jirachaya Yeemin used a range of technologies to identify and quantify molecules involved in the plant-bacterium interaction. Jaramillo and Ho-Wen Yang conducted additional experiments to validate Fochs' results.

© Maeli MelottoGraduate students involved in the research include, from left, Brianna Fochs, Jirachaya "Best" Yeemin and Ho-Wen Yang. Fochs is the lead author on the paper and is now a senior scientist at Genvor Inc. Yeemin is now an assistant professor in the Department of Biology at Ramkhamhaeng University in Bangkok, Thailand

© Maeli MelottoGraduate students involved in the research include, from left, Brianna Fochs, Jirachaya "Best" Yeemin and Ho-Wen Yang. Fochs is the lead author on the paper and is now a senior scientist at Genvor Inc. Yeemin is now an assistant professor in the Department of Biology at Ramkhamhaeng University in Bangkok, Thailand

Funding for this research came largely from National Institute of Food and Agriculture, part of the United States Department of Agriculture. One of the institute's priority research areas is breeding food crops for greater safety.

Auxin is the trickster, but how?

Leaves have tiny pores on their surface called stomata, which open and close for all kinds of fundamental plant processes. When harmful microbes try to get in through the stomata, the plant employs a defense called stomatal immunity.

Melotto calls it, "the fight at the stomatal gate." The plant detects the bacterium's flagella – the long, hair-like propeller the bug uses to swim. There ensues a pattern of open-close-open as the plant and pathogen square off.

Back in 2005, Melotto first discovered this mechanism when plants are attacked by the bacterium Pseudomonas. Years later working with Salmonella, people in her lab found the same pattern but suspected a different underlying mechanism. The team launched all kinds of exploratory experiments, comparing infected and non-infected plants while looking at metabolic pathways and screening for genetic connections.

They found clues pointing to the hormone auxin as the signal involved in re-opening the stomata. Fochs started more-targeted experiments and proved auxin is the messenger that tells "guard cells" surrounding the stomatal pore to open up. The team also found that plants close their stomata about two hours after detecting the presence of Salmonella, then the stomata reopen at about four hours.

© Trina Kleist/UC DavisMaeli Melotto is a professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences. Much of her team's work is conducted in a lab specially equipped and certified to handle biological hazards

© Trina Kleist/UC DavisMaeli Melotto is a professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences. Much of her team's work is conducted in a lab specially equipped and certified to handle biological hazards

It's not clear how biosynthesis of auxin is triggered, nor who is triggering it: Both plant and bacterium produce the hormone, Melotto said. The chemical pathway also remains a mystery – for now. "We think it's being induced through tryptophan, the precursor to auxin," Melotto said. "But what induces the tryptophan pathway, we still don't know."

Melotto and team also conducted some research with lettuce. In a related project now, the team is zeroing in on lettuce to study the chemical pathways and related genes that could tell them how to breed leafy greens to resist Salmonella. It's tricky, because manipulating the auxin signal is complex.

"There's still a long ways to go," Melotto said.

Source: UC Davis