At the University of Hyderabad, rows of carefully cultivated tomato plants represent far more than an agricultural experiment. They embody a two-decade-long national effort to strengthen India's research capabilities in plant genomics and crop improvement. At the heart of this effort lies the Repository of Tomato Genomic Resources (RTGR) — a facility that has become a national centerpiece of innovation and excellence in tomato research.

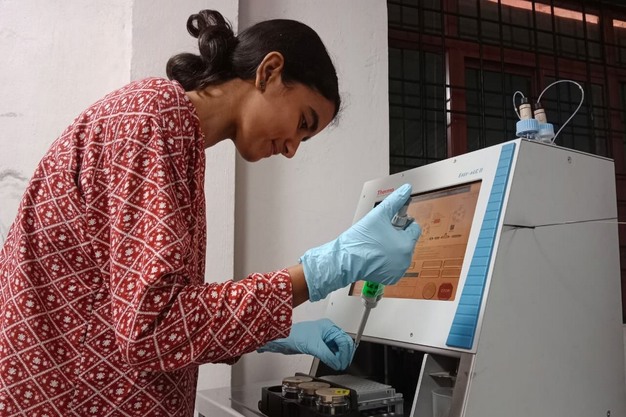

Established in 2010 by the University of Hyderabad with support from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India, RTGR was envisioned as a comprehensive platform for developing and maintaining genetic and mutant resources of tomato. Over the years, it has evolved into a Centre of Excellence for Genome Engineering in Tomato, equipped with state-of-the-art facilities for genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

"Our goal is to improve the nutritional value and shelf life of tomatoes without compromising their flavour and texture," says Prof. Y. Sreelakshmi, Department of Plant Sciences, who leads RTGR's research initiatives. "We are combining molecular, metabolic, and physiological approaches to create tomato varieties that are rich in nutrients and capable of lasting longer after harvest."

© University of Hyderabad

© University of Hyderabad

Building a national resource

RTGR was established with a dual mission: to advance scientific discovery in tomato biology and to provide shared infrastructure for researchers across India. The facility houses extensive genetic collections, analytical equipment, and bioinformatics resources that support both in-house projects and external collaborations.

"The DBT funded our infrastructure and continues to support research and training," says Prof. Sreelakshmi. "After the initial project ended, we were encouraged to sustain the facility by offering analytical and research services. This has allowed us to extend the use of our equipment and expertise to universities, research centres, and industries."

Through the SAHAJ Infrastructure Scheme, RTGR provides advanced metabolomic and proteomic analysis services to academic and industrial partners. The centre also distributes genome-sequenced EMS-mutant seed lines under the DBT Centre of Excellence to researchers from other academic institutions.

"We have shared mutant seed lines with Tamil Nadu Agricultural University; NISER, Bhubaneswar; SRM University-AP, and we are finalising an agreement with Kagome, a Japanese company," notes Prof. Sreelakshmi. "The intellectual property remains with us, but collaboration allows these materials to be tested and applied in real-world agricultural contexts."

Scientific innovation and discovery

RTGR's research covers a broad range of scientific questions related to fruit development, ripening, and nutritional enhancement. Among its most notable achievements is the identification of a dominant-negative mutation in the phototropin gene (phot1), which leads to enhanced carotenoid accumulation in tomato fruits.

© University of Hyderabad

© University of Hyderabad

This discovery, published in The Plant Journal (2021) as "A dominant-negative mutation of phototropin enhances carotenoid content in tomato fruits," demonstrated how manipulating light response pathways can increase levels of lycopene and β-carotene — both critical for antioxidant and provitamin A activity.

"The mutation modified the plant's light perception mechanism, indirectly enhancing pigment biosynthesis," explains Prof. R. P. Sharma, Emeritus Professor at RTGR. "It is an example of how understanding basic plant physiology can lead to tangible nutritional improvements."

In addition, RTGR has developed both delayed- and early-ripening tomato mutants through genetic modulation of ethylene pathways, addressing the challenge of post-harvest loss — one of the most significant issues in the Indian tomato supply chain.

"Some of our lab-grown tomatoes can stay fresh for 15 to 20 days at room temperature," says Prof. Sreelakshmi. "In some cases, under controlled conditions, they have remained intact for much longer while retaining nutritional quality."

Sustaining research and training

Like many advanced research facilities in India, RTGR operates within the constraints of limited funding and modest infrastructure support. Sustaining field trials, maintaining greenhouses, and conducting high-cost analyses require continuous effort and financial planning.

© University of Hyderabad

© University of Hyderabad

"We rely largely on competitive research grants," says Prof. Sreelakshmi. "Every project proposal we write is essential for maintaining our operations, training students, and continuing experimentation. The cost of consumables, maintenance of equipment and greenhouses, and fieldwork is substantial. The Department of Biotechnology's support through research grants is the key backbone for the successful research output of RTGR."

To promote scientific capacity-building of young scientists, RTGR organizes workshops and training programmes on metabolomics, proteomics, and data interpretation. These sessions, supported by DBT grants, provide hands-on experience to PhD students and early-career researchers.

"We focus on meaningful training," Prof. Sreelakshmi explains. "Participants must demonstrate how they will apply these techniques in their own work. Our aim is to create skilled researchers who can independently use these advanced tools in plant science."

Bridging the research-industry gap

While the scientific progress at RTGR is well recognized, translating research outputs into industrial or commercial applications remains a persistent challenge.

"Many companies express interest after we publish our findings, but few follow through with investment," says Prof. Sreelakshmi. "Ironically, the same firms fund similar projects abroad. There is still a lack of willingness to support long-term research within India, despite government efforts to encourage academia–industry collaboration."

© University of Hyderabad

© University of Hyderabad

Despite these limitations, the center continues to explore partnerships and seeks to expand its engagement with both public and private stakeholders. The researchers believe that improved communication between scientific institutions and agricultural enterprises could accelerate the application of these technologies in the field.

Future directions

Looking ahead, RTGR's research agenda extends beyond nutritional enhancement. The team is currently investigating climate-resilient and space-efficient tomato plants, focusing on modifying plant architecture to optimize yield under high-density plantation systems.

"We are examining how to design plants that can thrive in less space and under variable climate conditions," says Prof. Sreelakshmi. "Given environmental uncertainties, this line of work is increasingly important for sustainable agriculture."

Prof. Sharma adds that the methodologies developed at RTGR have broader applications across crops. "The same genetic and biochemical approaches can be adapted to other species. What we are doing in tomato can be a model for crop improvement elsewhere."

Source: University of Hyderabad