The United Kingdom currently grows less than 20% of its fruit and around half of its vegetables, leaving it highly dependent on imports and vulnerable to climate shocks, market volatility, and global disruptions. A new study led by Dr. Sven Batke, Head of the Greenhouse Innovation Consortium at Edge Hill University, argues that the UK's path to food security lies not in expanding farmland but in modernizing and expanding its greenhouse infrastructure.

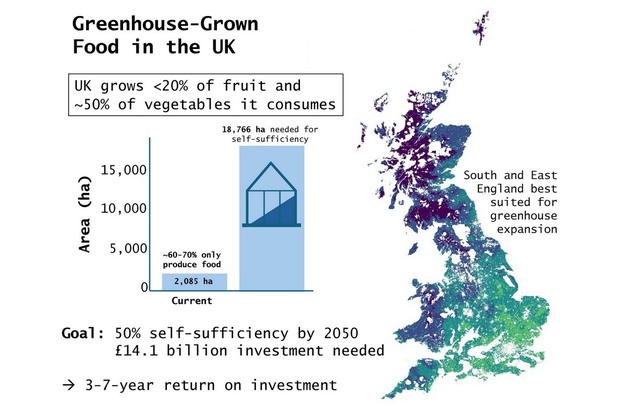

Published in Plants, People, Planet, the study mapped 2,085 hectares of existing greenhouse space across the UK. Worryingly, over 70% of this infrastructure is more than 40 years old, built in an era of cheap energy and outdated economics.

"Many of these structures are not fit for modern systems," Dr Batke says. "The focus must now be on energy performance, decarbonization, and environmental control." He emphasizes upgrades such as better glazing, insulated sidewalls, thermal screens, and advanced ventilation.

Heating remains the sector's biggest expense and carbon source, with growing interest in heat pumps, district heating, and industrial waste-heat recovery. Meanwhile, shifting from HPS to adaptive LED lighting reduces energy use and improves crop uniformity.

© GIC

© GIC

Retrofits with quick returns

While large-scale redevelopment may seem daunting, many improvements offer fast, cost-effective gains. "Upgrading thermal screens can pay for itself within two years," he notes. Replacing lamps with LEDs or improving airtightness also delivers immediate savings.

Closed-loop irrigation and fertigation systems are becoming standard, improving efficiency and meeting new Environment Agency rules on nutrient discharge. In regions such as East Anglia and the Humber, integration with industrial waste heat is already commercially viable.

"With energy forming such a large part of production costs, any investment that lowers energy per kilogram of produce strengthens the business case," he says. Some growers are even trialing semi-transparent photovoltaic glazing, allowing greenhouses to generate their own electricity.

© GIC

© GIC

The economics of self-sufficiency

To reach 50% self-sufficiency in greenhouse-grown fruit and vegetables by 2050, the UK would need to quadruple capacity, requiring around £14.1 billion in investment. Yet, the returns are promising — a payback period of 3–7 years, driven by reduced imports and domestic market demand.

"When we compare costs with imports from the Netherlands, Spain, and Morocco, and factor in savings from shorter supply chains and less waste, the economics make sense," Dr. Batke explains. With modern low-carbon systems, payback could be even faster.

The geography of growth

The South and East of England are best suited for greenhouse expansion thanks to 20–30% more solar radiation, milder climates, and proximity to retail hubs. However, high land values mean expansion must be strategic.

By contrast, the North and Midlands present opportunities for heat-integrated greenhouses linked to industrial clusters, biogas plants, or wastewater facilities. "These projects can operate with very low energy costs and bring regional benefits — skilled jobs, diversification, and access to fresh food in so-called 'food deserts'," he says.

Using greenhouse horticulture to support leveling-up goals could have long-term social and economic impact.

© GIC

© GIC

Financing and policy: A national infrastructure approach

Achieving the £14.1 billion investment target requires blended financing, combining private capital, grower equity, and public-sector support. Batke suggests government-backed guarantees or low-cost loans through the UK Infrastructure Bank could accelerate deployment, especially for renewable-integrated projects.

"To attract investors, the sector would benefit from a revenue stabilization mechanism, similar to the Contracts for Difference scheme in renewable energy," he says. Without a coordinated national policy, the UK risks falling behind the Netherlands and other leaders in protected horticulture.

Crucially, he believes greenhouse horticulture should be classed as national infrastructure. "It supports food security, decarbonization, and circular resource use — for heat, CO₂, and water. It deserves the same strategic recognition as energy or water infrastructure."

© GIC

© GIC

Preparing growers and councils

For growers, his message is clear: be project-ready. "Secure permissions, grid or heat connections, environmental studies, and business plans. Cooperative models and regional clusters can make investments more viable, especially when infrastructure like heat or CO₂ networks is shared."

Local councils also play a critical role. They can help by designating agri-tech zones or issuing Local Development Orders to streamline planning while maintaining environmental standards. "Transparency and community engagement are essential for public acceptance," he adds.

Looking ahead: Automation and AI

According to Dr Batke, the next generation of greenhouses will be defined by automation and data intelligence. "AI systems are already analysing sensor data and adjusting climate conditions in real time." Automation won't replace experienced growers but will allow them to manage complex systems with greater precision.

Although adoption is uneven, facilities using digital control systems are already achieving major gains in energy efficiency and yield. "Data-driven decision-making will become the hallmark of advanced UK greenhouse operations," he predicts. "The real challenge lies in overcoming the behavioural and political barriers that slow innovation."

Dr. Batke envisions a future where greenhouses form a circular, low-carbon food economy. "By mid-century, I hope greenhouses will be recognised as essential nodes in the UK's food network," he says. "They'll deliver stable supply, cut waste, and act as hubs for energy and resource management, making it all the more sustainable."

For more information:

Dr. Sven Batke, Chair of the Greenhouse Innovation Consortium

[email protected]

edgehill.ac.uk/person/sven-batke/staff/