On July 14, the Trump administration terminated the 2019 Tomato Suspension Agreement, which governed Mexican tomato exports to the United States since the first such agreement was signed in 1996. The agreement established a floor price for Mexican tomato exports to the United States. During its nearly three decades in existence, the agreement ensured a stable and expanding market, providing U.S. consumers with year-round access to a wide variety of tomatoes. The suspension agreement was renegotiated in 2002, 2008, 2013, and 2019 under both Republican and Democratic administrations, with a focus on enhanced enforcement. In April 2025, however, the Trump administration announced its intent to terminate under Section XI.B of the agreement. The decision will impact the volume of Mexican tomato exports, the U.S. companies that import and sell the tomatoes (primarily in Texas and Arizona), consumer price and choice, U.S. domestic production (including raising further questions about the availability of adequate labor), and the U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationship more broadly.

Background

The original Tomato Suspension Agreement entered into force in 1996 and suspended the antidumping investigation initiated by the U.S. Department of Commerce in response to a petition filed by U.S. tomato growers and packers alleging that Mexican growers were selling their tomatoes at prices below fair market value. Extensive negotiations between the Department of Commerce and the Mexican tomato industry, supported by the Mexican government, concluded with the signature of the agreement. Under its terms, the Department of Commerce agreed to suspend its antidumping investigation, and in return, Mexican growers and exporters agreed to sell their tomatoes in the United States at or above established minimum prices or "reference prices."

Upon terminating the agreement, the Department of Commerce implemented an antidumping duty order on all imports of fresh tomatoes from Mexico, applying an average import duty on Mexican tomatoes returns of 17.1 percent—the rate established through the 1996 investigation. While consumers may see multiple varieties of tomatoes in their grocery store, all tomatoes have the same classification (0702) under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States. In other words, a tomato is a tomato, regardless of the variety (e.g., grape, Roma, or common round). Nevertheless, the Tomato Suspension Agreement established a floor price in U.S. dollars per pound for distinct varieties and distinguished between organic and "other than organic" fresh tomatoes. Signatories agreed not to sell their products to the United States for less than the applicable floor price. Though perhaps counterintuitive, termination of the agreement could lead to lower tomato prices for U.S. consumers in the short run since exporters are no longer bound to sell their tomatoes at a minimum price. The tariff is applied on the declared or entered value of the tomatoes, which can vary depending on supply and demand, like any other traded commodity.

Pressure to withdraw from the agreement was directed at the Department of Commerce virtually since the agreement first entered into force in 1996, though opposition to the agreement has never been unanimous within the U.S. tomato industry. Clear divisions exist between southeastern growers and western growers and importers. Indeed, comments and formal submissions by various industry players showed clear differences of opinion during the 90-day period between the Trump administration's announcement of its intent to withdraw and the termination of the agreement on July 14. In past reviews of the agreement, the western stakeholders, importers represented by the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas (FPAA), and other business and industry groups, successfully convinced past U.S. administrations to renegotiate. With some changes and tweaks, the agreement was renewed four times, despite opposition, primarily from Florida tomato growers represented by the Florida Tomato Exchange (FTE) and from other southeastern growers.

© Joe Raedle/Getty Images

© Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Differences between the eastern and western U.S. growers, including in their business models and the tomato varieties they produce, influence their views on the agreement. Southeastern growers are mostly known for the production of round or beefsteak tomatoes—the type often used by fast-food and casual dining restaurants—though the FTE notes their members produce other tomato varieties as well in Florida and along the U.S. East Coast. These round tomatoes are uniform in shape, are picked green, and then treated with ethylene gas to ripen. Florida's tomato industry employs roughly 30,000 workers in Immokalee and Collier counties, many seasonally employed. At 51,000 in FY 2023, Florida had the largest number of certified seasonal farm jobs (those filled by H2-A, nonimmigrant agricultural worker, visa holders).

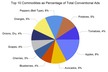

In the western United States, domestic growers and importers are now deeply integrated with Mexican suppliers, with firms often operating on both sides of the border to produce and/or import a wider variety of tomatoes (e.g., Roma, grape, and cherry) than their eastern competitors. Analysis conducted at Texas A&M University's Center for North American Studies found that the import of Mexican tomatoes is responsible for nearly 25,000 direct jobs in the United States and nearly as many indirect or induced positions. In FY 2023, California had 40,000 certified seasonal farm jobs.

Production in Mexico

Tomato exports are a significant source of income and jobs for Mexico. Since 1995, Mexican exports of fresh tomatoes to the United States have grown substantially from 1.3 billion pounds in 1995 to 4.4 billion pounds in 2024 or, in value terms, from $406.0 million to $3.1 billion. Mexico accounts for roughly 90 percent of U.S. tomato imports. With the integration of operations on both sides of the border, firms have frequently sought and obtained temporary worker visas under the H2-A program to harvest their crops. The workers often work for the same firms in both countries, moving north in the summer and returning to work in Mexican fields in the winter. This has both provided them with a steady source of income for their families, which may contribute to reduced pressure to migrate. In addition, the integration of the markets has ensured that U.S. consumers have access to a wider variety of tomatoes year-round.

Differing perspectives

Growers in the southeast have consistently opposed the agreement, arguing, "Since 1996, the FTE has led the U.S. industry in fighting against low-priced and subsidized tomato imports, which have significantly injured tomato growers across the country." With respect to the 2019 agreement, FTE notes on its webpage that, "The suspension agreement that was renegotiated in 2019 was supposed to close the loopholes that had rendered the previous agreements ineffective. Unfortunately, the 2019 agreement has also proven to be unenforceable and easily violated by Mexican dumping." The Trump administration's decision to terminate the tomato suspension agreement was applauded by 19 members of the Florida congressional delegation in a June 20 letter to Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick.

Growers and importers in the west, which often operate binationally and have traditionally supported the agreement, argued that its termination would cause U.S. consumers to "pay significantly more for their preferred vine-ripened, specialty and [Roma] tomatoes if duties . . . go into place." The FPAA also asserted that the innovations brought to market by its members throughout the tomato suspension agreement period allow consumers to now "shop for a wide array of vine-ripened grape and cherry tomatoes, tomatoes on the vine, [Roma] tomatoes, and other specialty tomatoes" and questioned whether such innovation would continue.

Opposition to the termination was not limited to western growers and importers but also included a wide range of national and local organizations, such as chambers of commerce and producer and consumer associations, over 30 of which signed a letter from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to Secretary Lutnick opposing termination and instead calling for renegotiation of the agreement. Members of Congress representing western states, including Arizona Senator Mark Kelly, also wrote to Secretary Lutnick in opposition to the termination, expressing concern about potential job losses.

Mexico's response

When the Department of Commerce announced its intention to terminate the tomato suspension agreement in April 2025, the Mexican government, led by Secretary of Economy Marcelo Ebrard and Secretary of Agriculture Julio Berdegué, accompanied Mexican industry representatives in seeking to negotiate an extension. The officials asserted that industry had offered constructive proposals that were rejected for "political reasons." Once the termination was official, the Mexican Secretaries lamented the decision, which they characterized as "unfair and contrary to the interests of Mexican producers and U.S. industry."

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum rejected the Department of Commerce's decision but insisted that Mexico would continue to export, even with a tariff, because there is "no substitute." She also indicated that Mexico would announce steps the government would take in conjunction with Mexican producers in the context of her administration's development plan, known as Plan Mexico. On August 8, Secretaries Ebrard and Berdegué published in the Diario Oficial de la Federación an agreement supported by all of Mexico's tomato export associations to establish a minimum export price for tomatoes. According to the secretaries, the agreement "seeks to protect the national production plant, avoid distortions in the international market and guarantee supply to domestic consumption."

Next steps

In the United States, tomato prices have remained fairly steady since the suspension agreement was terminated, based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Tomato Fax Report. Summer is, of course, the peak season for domestic tomato production on both the East and West Coasts, which correlates with lower import volumes from Mexico. The true impact of the termination will likely become apparent later in the year when Mexican tomato production and resulting exports traditionally increase and offset reduced domestic production. Absent a new agreement, Mexican fresh tomato imports are subject to the 17 percent duty based on the value of the shipment. If exporters choose to reduce prices below the former price floor, consumers may see lower prices than under the suspension agreement, even with the duty applied. Other analysts, however, suggest that since domestic producers cannot quickly ramp up production, if Mexican tomato exports decline, the resulting supply gap will lead to price increases.

The supporters of the decision to terminate the agreement have argued that unfair trading practices on the part of Mexican tomato growers suppressed the market and made it uneconomical for U.S. producers. The absence of the agreement will, they hope, lead to increased opportunities for domestic production. This, however, raises a secondary issue—labor.

The United States currently faces labor shortages in the agriculture and food production sectors and relies heavily on migrant labor. Indeed, fewer than 60 percent of crop workers were authorized to work in the United States, according to a 2023 survey prepared for the U.S. Department of Labor. Though many farms employ authorized workers under the H2-A visa program for seasonal agricultural workers, the number of visas issued by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is generally lower than the number of positions certified by the Department of Labor due to USCIS processing constraints. Given the reliance on migrant labor (both authorized and unauthorized) in the United States and decreasing U.S. fertility rates, Secretary of Agriculture Brook Rollins' July 8 prediction that the current mass deportation strategy of the Trump administration would lead to a "100 [percent] American workforce" seems improbable at best. Lack of available workers also leads to lost revenue as ripe fruit and vegetables rot before they are harvested.

In Mexico, following the July 14 termination, President Sheinbaum promised to announce steps to support her domestic industry and to continue to negotiate with the United States. She also said that if an agreement was not reached by August 1, the government would have to take "other actions." As noted, one week later, Mexico announced an export price floor, presumably to try to recreate the status quo ante. A potential additional step would be to help identify new markets to reduce reliance on the United States, perhaps taking advantage of Mexico's extensive network of free trade agreements. At the same time Mexico seeks actions to ameliorate the impact of the termination on its tomato growers, it is likely that Mexico (and allied U.S. stakeholders) will continue to press to negotiate a new agreement to provide certainty in the tomato market.

Implications for the US-Mexico bilateral relationship

The Tomato Suspension Agreement is not the only stressor (commercial or otherwise) impacting the U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationship. The Trump administration's decision to grant a 90-day delay in the imposition of threatened tariffs on Mexico's non-USMCA-compliant exports suggests recognition of the importance of this relationship for the United States as well. Nevertheless, the Trump administration's decision to terminate the long-standing suspension agreement, rather than negotiating an update, underscores its willingness to impose tariffs even when doing so may harm U.S. consumers and U.S. labor conditions. As the Sheinbaum administration prepares for the review of the USMCA next year, while simultaneously working to forestall the application of a 30 percent tariff on non-USMCA goods (and potential sectoral tariffs), it surely will consider the Trump administration's decision to terminate the Tomato Suspension Agreement. The decision, described by Mexican officials as "political," should be a reminder that Trump primarily views the bilateral relationship in strictly domestic terms, not the more traditional "intermestic" view offered by U.S. administrations over the past 20-plus years.