Grafting can be applied to all vegetable crops such as tomatoes, eggplants, cucumbers, courgettes, peppers and watermelons. Today, grafting has transferred from a challenge into standard practice, even though it is and remains an 'operation' that must be carried out with extreme precision. Hans van Herk of Propagation Solutions discusses the matter in detail below.

As a cultivation consultant, Hans van Herk focuses specifically on plant propagators

There are various reasons for grafting. Usually, resistance to diseases or extra growth power are the main reasons. This means that more stems and/or fruits can be held, more CO2 can be used and the cultivation can be continued for longer. All this leads to higher productions.

From challenge to standard practice

Grafting is an old trick these days, but reinvented itself in the late 90s. The introduction of new rootstocks in tomato that, in addition to resistances, gave extra growing power to the crop became a great success. Tomato and eggplants in particular benefited enormously and productions went up considerably as a result of the points mentioned above. Credit for product development must certainly go to the eggplant growers in the Netherlands since they were the first to combine the vigour of the rootstock with the fruit quality of the varieties.

Furthermore, it also became much more interesting for plant propagators to graft tomatoes, because the so-called 'Brielse grafting method' was replaced by the 'Japanese head-to-head grafting method'. This method provided much more speed, efficiency and a better success rate and has become the standard worldwide.

Head-to-head grafted tomato seedling above the cotyledons

However, the challenge is still there for other crops such as bell pepper and cucumber. Outside organic cultivation and soil cultivation, these crops are not grafted, even though there are substantial areas of these crops. At this moment, there are hardly any rootstocks that can bring these crops to a higher level in terms of production on the basis of vigour. At the moment, it is only a matter of resistance.

Watermelon as an exception

The big exception, which is (almost) not cultivated in the Netherlands, is the watermelon. Huge areas are cultivated in Southern Europe, Mexico, the United States, Australia and the Middle East. Fusarium oxysporum is the soil-borne disease that makes grafting necessary. However, watermelon is a tricky one and the various types (seedless, micro-types) make it even trickier. Also the rootstocks are much more difficult to match with the varieties as they are genetically very different: Pumpkin types (Cucurbita maxxima x mosschata) and Lagenaria types (Lagenaria vulgaris) are used. Furthermore, the taste of watermelons is also influenced by the rootstock. A far-reaching specialisation in terms of the combination of rootstock and variety has therefore been implemented.

Watermelons cannot be grafted using the Japanese head grafting method, so a variant of 'suction grafting' is applied. This involves using the cotyledon leaf of the rootstock and both cotyledon leaves of the watermelon. The roots are also removed to reduce root pressure. This creates a complex combination of two plants on which all sorts of actions have been carried out. The numbers per hour are therefore considerably lower compared to the grafting of tomatoes or eggplants.

Grafted watermelon the cotyledon of the rootstock

Keeping the plants compact is not easy either, which is a real customer wish from the end users who often grow the watermelon in an agricultural way. Compactness is obtained by using the right planting age for grafting.

Watermelon plants stretch easily in the growth space due to the high moisture content required for growth, but this can also easily become a disadvantage. A tight focus during the growing process to avoid moisture problems is essential.

Growing and healing the graft

The healing of the wound created by cutting two plants and re-joining them together is very similar to human surgery and the recovery period in a hospital. The grafting situation must be clean and sterile. The conditions after the operation must be comfortable and without triggers. All this to have full focus on the recovery of the wound.

If this is translated into the plants and their circumstances, the following things are very important immediately after grafting:

- High humidity (100%) to stop evaporation;

- Leaf-wetting period to strengthen it;

- Comfortable and even temperature (23°C D/N);

- No influences that stimulate evaporation such as radiation and wind.

Diameters of the stems should be reasonably equal, which is a custom job and can vary by season and location. The methods for creating these conditions are diverse. The following are common:

1. Plastic tunnels

Two examples of tunnels made in the greenhouse; a curved tunnel or a flat tunnel. The horizontal one is preferred because temperature and humidity are the same for all plants. It is quite conceivable that this does not apply to the curved tunnels if the middle is compared to the side. This would influences the uniformity of the plants.

Advantages of this system are its low costs and flexibility of location. Disadvantages are that many influences (temperature and wind) can worsen the stable climate in the tunnel.

Horizontally flat tunnels with a simple but efficient structure of pvc-pipes

2. Climate cells

In an ideal situation, temperature and humidity can be controlled to within 0.1°C and 1%. For this, a climate cell should be perfect. The advantages are that it is more efficient in terms of the number of plants per square metre and that there is no influence from radiation or wind. The disadvantages are that the system is more expensive and that several cells are required if several weeks of grafting are involved.

Striking success

Details determine the degree of success, although in tomato it is often at high levels. Watermelon has 80-85% as a standard because it is more difficult. The moment to start acclimatisation and to bring the 'patient' back into 'the real world' is a 24/7 job; it continues through weekends. Slowly, the humidity has to be brought down in small steps; for cucumber, this often works with 1%, other crops can handle bigger steps (3-5%). The temperature remains the same because this is the engine of the process. If it is lowered, the healing process slows down as well.

On the first day of acclimatisation, the plants will quickly wilt recognisable by the hanging cotyledons and the dark green colour of the heads. Then the tunnel should be closed quickly so the RH increased to limit evaporation again. On the first day, this can be as little as 20-30 minutes.

On the second day, acclimatisation may take a little longer, say 2-3 hours. But even then, the same symptoms will appear, indicating that there has been enough evaporation and that a shortage is likely to occur.

On the third day, the acclimatisation could last all day and the symptoms only return at the end of the day. The humidity must then be brought back to a level where evaporation is minimal.

On the fourth day of acclimatisation, usually 6-7 days after inoculation, the process is almost complete and the wound has healed. The humidity can definitely be brought back to 70-75% and the plants should be able to function normally again.

Usually, one extra day is good for the recovery, so that the step to the next process called transplanting, can be taken properly. The plants go down to a much lower density (from about 400 pl / m² to about 75 pl / m²). No small step, so take your time, Hans advises.

Technique of acclimatisation

Acclimatisation of the tunnels can be done in two ways, either by making cuts in the plastic in a regular way or by opening the tunnels completely.

Making cuts is relatively uneven for the plants, throwing open the tunnel is a fairly firm measure. The advantage of opening the tunnel completely is that it is very uniform, the disadvantage is that one almost literally has to stand by.

The first method, besides the unevenness in terms of humidity for the plants, also has a greater risk of stretching. This is highly undesirable as compactness is an important customer requirement, and stretching is very difficult to rectify later.

Symptoms of healing = acclimatisation

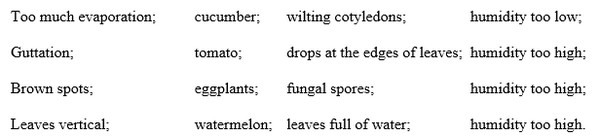

The plants cannot talk, but they do show when the healing has taken place. Through physiological processes, that is. Examples are:

If these last three symptoms are visible, then it is clearly time to start acclimatisation or to speed up/enlarge the steps. Often, a protocol is used to start acclimatisation after 3-4 days. This is fine, but there are also exceptions. Varieties can fit well with a rootstock or it is simply a perfect combination at that moment. In that case, you can certainly start a day earlier and follow the same standard protocol, only one day faster. For this, a twice-daily control is indispensable, which will also have to be done in the weekends.

Good grafting results

For a propagator, good grafting results are indispensable; all the costs have already been made. At the same time, making up for deficiencies by re-seeding results in a considerable backlog compared to the rest of the batch, which can no longer be made up.

In making uniform batches of plants the following is essential:

- Good coordination of the age of the rootstock and the variety;

- Quality rootstocks (a lot of energy, compact, many roots, dark green leaf colour);

- Discipline staff regarding the grafting itself in terms of hygiene and assembling the 2 plants;

- Good conditions for the plants to grow;

- A well-trained staff to determine the right moment of acclimatisation.

Hans concludes that it is good that grafting vegetable plants has become standard for many crops in the last decades. Hopefully, it will also be possible to have the grafting success on a high quality level but specifically to keep it there.

For more information:

Hans van Herk

Propagation Solutions

+31 (0)6 20 91 81 00

hans@propagationsolutions.nl