The abbreviation in the title now needs no explanation in tomato land. Two years after the first official virus discovery in the Netherlands, everyone who grows, breeds, packs, or trades tomatoes has to deal with the tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV), either because of an infection in their own greenhouse, or simply because it influences the market so heavily. This summer, for example, ToBRFV infections caused tomato shortages that resulted in 'winter prices'. The virus is also expected to have an impact on the market in the coming season, because plantings are disrupted and production peaks will occur at other times.

ToBRFV symptoms in a German greenhouse in 2018. Photo by Heike Scholz-Döbelin with Eppo.

All these changes in growing and demand can be described as the 'ToBRFV effect', which was pronounced for the first time this summer, at least in the tomato trade. It can be explained by the fact that the infection numbers have risen sharply and thus the virus has spread considerably.

For growers and breeders, the virus has been a hot topic and a major cause for concern for some years now. Since the first official finding of ToBRFV in the Netherlands in spring 2019, the virus has rapidly spread worldwide. The virus is easily transferable and "highly persistent," as it is called among virus specialists: the virus can survive for long periods without a host plant in the greenhouse, for example on clothing or on barrels.

In 2018, the virus surfaced in Germany, while the scientific literature on the virus lists Israel as the first place the virus was found in 2014. The plant virus is not dangerous for humans and animals, but it is dangerous for peppers and especially tomatoes. The fact that the virus is harmless to humans and animals was emphasized as soon as the first reports of the virus began to circulate, which is only logical, for as soon as ToBRFV started to become serious in the Netherlands, people became scared. A virus and the consequent negative publicity for tomatoes, as everyone in the tomato world who also experienced the Wasserbombs crisis in the 1990s knows, can cause major (financial) damage. What if consumers decide not to buy tomatoes (from the Netherlands) anymore out of unjustified fear of the virus?

Q-status

It did not come to that in recent years, but it did remain, especially in 2019, very quiet around the virus. So quiet, in fact, that several specialists from the Netherlands felt compelled to call on the market in the course of 2019 to share information in particular. René van der Vlugt was one of them in July 2019. "Without clarity, there is no real action, yet that is what is desperately needed," he noted. René underlined the importance of caution in reporting about viruses in greenhouse horticulture, precisely because of trade and political interests, but also stressed that ToBRFV, as a persistent virus and a real threat, should be taken seriously.

In March 2019, the first rumors of ToBRFV discoveries on Dutch soil began to circulate. However, it was not until October that a report of an officially confirmed infection was made. Not long after, as of November 1, 2019, the virus was given European quarantine (Q) status. This means that it has become mandatory to report to the authorities in case of (suspected) infection. Even before it came to a Q-status, the Netherlands was not in favor of such a status because of the "lack of clarity" about the virus at the time and the fact that culling a greenhouse has a "considerably larger impact on a tomato company than the virus itself," an NVWA spokesperson put it in May 2019.

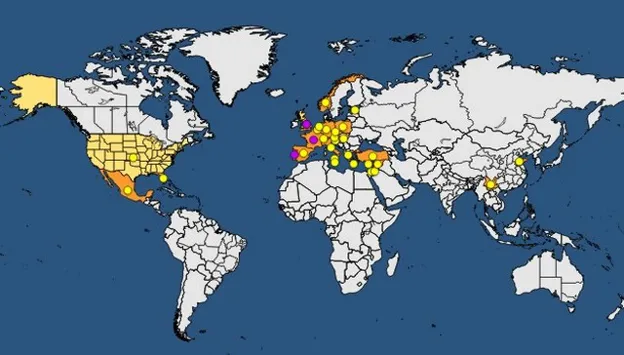

Spread of ToBRFV worldwide, as tracked by EPPO on a map

With today's knowledge, there is much more clarity about the spread of the virus, as evidenced, for example, by the frequently consulted virus spread map of the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO). Precisely because the virus is so widespread, the Netherlands continues to point out the disadvantages of the Q-status. That status weighs heavily on the Netherlands as a large but at the same time small player in terms of manpower when it comes to, for example, virus testing and tracing research. The NVWA and the National Plant Protection Organisation (NPPO) therefore hope to convince the rest of the European member states that, once the current Q-status expires in May 2022, (strict) requirements on seeds and plant material can also ensure the further spread of the virus.

ToBRFV counter

After the first official Dutch infections, the counter of ToBRFV infections, which the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) has been transparently keeping track of since then, has started to increase. The latest count, as of September 13, 2021, is that there are 29 infected farms in the Netherlands. In total, the virus has been identified at 41 cultivation sites since mid-2019. Growers who are infected come under supervision and have to start working with a package of officially determined hygiene measures. However, growers do not get rid of the virus overnight; growers have become accustomed to many viruses over the course of time, such as the tomato chlorosis virus (ToCV), but ToBRFV turns out to be an even more virulent enemy, if possible. Before ToBRFV made its appearance, there was a lot of buzz around ToCV in 2018, and there still is, as the Dutch virus control association HorticultureAlert emphasized that ToCV is still "latent" last Fall.

Several growers have now succeeded in eliminating the virus permanently; the NVWA speaks of 9 locations that officially 'eliminated' the virus in the figures of September 13. There is also 1 location where the virus returned, despite the fact that growers cleared the infected crop after infection and cleaned and disinfected the greenhouse. In the meantime, some growers have decided, because of the persistence of the virus, to switch to another crop, for example, cucumber. Such a switch is not something that growers are particularly keen to advertise, as talking about the virus remains difficult, but little by little, there is more openness. Tomato grower Leo van der Lans, for example, has been in the media several times this year (Algemeen Dagblad, WOS) to talk about the ToBRFV infection that continues to plague his business and which he does not think will be completely eradicated. "We will have to live with it," he told WOS in September. Growers report harvest losses to the NVWA when there is an infection of 5 to 30 percent. They do not have to clear out their entire greenhouse, but the infected plants produce less and must be removed from the greenhouse to prevent further spread and greater damage. Fruit with virus symptoms are, from an aesthetic point of view, unsaleable.

Outside the Netherlands, it remained, officially speaking, quite quiet (too); there is no ToBRFV counter as kept by the NVWA abroad. The Belgian Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain (FAVV), for example, does not have such a counter, at least not in public - this is not a reproach, but an observation. The FAVV, like the NVWA and plant health services elsewhere, does share hygiene protocols, and, if asked, also contamination numbers. At the end of June, Belgium had 6 official contaminations among production growers (12 by the end of november). Meanwhile, the contamination map of the EPPO, even without ToBRFV counters, became increasingly colored. This year, in particular, one country after another is reporting contamination. Often these are 'first finds', but countries like Spain also report new infections.

Solution

Since the end of last year, in addition to reports of infections, there have also been increasing reports of (future) resistant varieties. Several (large) breeding companies are busy adding resistances to varieties in their laboratories and demo greenhouses. However, this is not a simple, let alone a fast process. Breeding, as always, takes time. Meanwhile, breeding companies have gained insight into a gene that adds an 'intermediate' or 'high' resistance to ToBRFV to a tomato, as it is called in breeding language. For other tomato viruses, such a gene proved to be a good solution. The higher the resistance, the fewer virus symptoms (discolored leaves, spots on a tomato) a plant will show. With the varieties, which are now being tested in many places, breeding companies are targeting countries such as Mexico and regions like the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Another 'solution' could be a vaccine, but as long as the virus has a Q-status, its production is (virtually) impossible and illegal, as was demonstrated in the Netherlands last September when the NVWA raided a location where attempts were supposedly being made to develop such a vaccine.

Photo shows a tomato infected with ToBRFV in the Netherlands. Photo by EPPO, Scientia Terrae Laboratorium

Growers are eagerly awaiting such solutions, although they are also realistic and expect new threats after ToBRFV. In the meantime, they are forced to adopt almost hospital-like hygiene practices on their farms. If you enter a tomato farm today, it is covered from head to toe and you are almost more likely to encounter laundromats than tomato plants. Growers have invested heavily in, for example, washing machines to wash the clothing of their staff, and also barrels undergo, even more than before, thorough washing with advanced installations. This washing of barrels is also a point of attention for trading and packaging companies, where (reusable) barrels go in and out. The advice for plant viruses and therefore also for ToBRFV is usually to separate the container flows as much as possible and to clean and disinfect the containers before they enter the company.

All these types of investments and hygiene costs, in addition to the constant threat of (re)contamination with ToBRFV and the resulting loss of production, weigh heavily on growers. On top of that, this autumn the energy crisis has hit. Electricity and gas prices have skyrocketed, causing growers to reconsider their strategy. Is it still worth turning on the lights full blast when the production costs are higher than the returns? The energy crisis on top of the ToBRFV situation promises an extraordinary (winter) season, which is perhaps the only certainty for now.