Since the birth of NAFTA in 1994, agriculture production in Mexico has more than doubled and the country continues experiencing tremendous production growth, now under the United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) agreement. As it continues to grow, yesterday’s PMA Virtual Town Hall--Mexico: Produce Powerhouse--examines developments and trends in Mexico’s agriculture.

As Rubén Ramírez, PMA general manager Mexico noted, in 2019 fresh fruit represented $6.9 billion and fresh vegetables represented $6.3 billion. “That is almost 50 percent of the total agricultural imports from Mexico,” says Ramírez.

Rubén Ramírez

Rubén Ramírez

Tomatoes

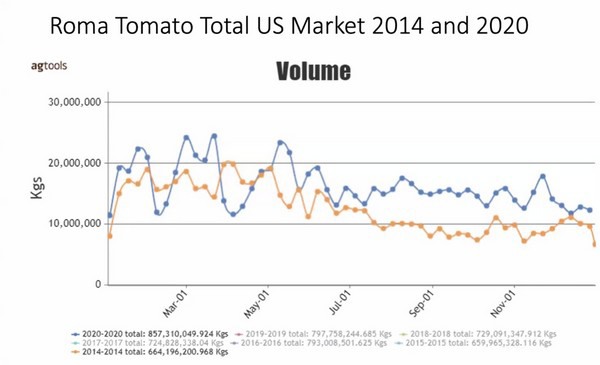

The town hall focused on some key crops Mexico has been developing, beginning with tomatoes. But even more so, Roma tomatoes.

“We went from 664 million kg. in 2014 to 857 million kg. in 2020,” says Antonio Villalobos, chief commercial officer, GR Fresh. Supporting that growth in tomato shipments of course is increased demand for tomatoes in the U.S. “Traditionally the U.S. is a round tomato consumer. But Roma tomatoes have been catching up. It tends to be tastier and has more flavor than other types of tomatoes,” says Villalobos.

Romas aren’t the only tomatoes seeing growth. Villalobos notes that round, grape, specialty tomatoes, tomatoes on the vine (TOVs) have also seen significant increased demand. And with that demand pushing production in Mexico, the country’s tomato production has also grown in sophistication. “There hasn’t been much added in total acreage grown. But the yields have grown in the past six or seven years due to technology,” says Villalobos. “Before you were able to get 5,000-6,000 cases out of a hectare and now you’re close to doubling that. It’s close to 12,000-13,000 cases depending on the cycle and area.”

That technology, including things like protected agriculture growing operations or high-tech greenhouses, have lengthened how many months Mexico can supply tomatoes, which is now year round. “The technology has allowed us to grow through the wintertime, which is probably when the U.S. market depends more on Mexican tomatoes. You only have mainly Florida growing at that time,” says Villalobos. “Traditionally you’d have the Pacific coast providing tomatoes out of Mexico. But now the year-round operations are from areas including Michoacan and Jalisco. Those areas have added a lot of mid and high-tech operations.”

Along with technological advancements, Mexico has also incorporated new varieties which offer better yields and lengthens that year-round availability which, in turn, allows customers to keep receiving tomatoes from the same growing region rather than moving through different locations in Mexico.

Berries

Another key Mexican crop, berries, is also seeing interesting developments. Starting with strawberries, Jose Luis notes that the growth in strawberries out of Mexico isn’t significant--it shipped about 836 million kg. of strawberries in 2014 and by 2020, that number reached 920 million kgs. “The strawberry market is fairly flat growing at about three to four percent every year,” says Jose Luis Bustamante, president of the board of directors of the National Association of Berry Exporters (Aneberries). “The room that is there is from November to March and that’s where Mexico is increasing its production and exports.”

Left to right: Jose Luis Bustamante, Antonio Villalobos

Left to right: Jose Luis Bustamante, Antonio Villalobos

Blackberries out of Mexico, the most mature industry out of the berry family, is also seeing stable supplies. But, like tomatoes, older varieties of the berries are being swapped out for better quality, higher yield new ones. “So I do see a change in blackberries once all the new varieties are in place,” says Bustamante.

Raspberries are also seeing steady growth in both demand and supplies. “Their varieties are also increasing and getting better production with higher yields which have less requirements on chill hours--such as low or no chill,” says Bustamante. “I think these will be the next blueberries.”

Indeed, that’s where Mexico is seeing its largest jump in both production and demand--the blueberry category. “With blueberries, in the spring window and autumn, there are spikes on the market. But also when the pandemic hit, blueberries became one of the most desired items to eat because of their health benefits,” says Bustamante. “There was increased consumption of them.”

Variety development has also taken place in Mexico leading to better quality and better yielding blueberries. “And contrary to other berries such as raspberries or blackberries, the shelf life is better and they’re easier to distribute,” says Bustamante, noting blueberries in Mexico is still a relatively young industry that’s largely seen growth in the past decade.

Looking ahead, Bustamante notes that the berry industry at least is looking to diversify and add new consumers. “We have a difficult hurdle which is the logistics--shipping berries to Asia will be only by plane. Blueberries have a good chance to travel,” he says, noting that the Mexican domestic market is also seeing increased demand for Mexican-grown berries.

Universal issues

And, like U.S. and Canadian growers, there are universal challenges Mexican growers have also faced. “Labor is the number one. Every year it’s been more of a challenge to secure the labor we need and add the pandemic in, it has made it a lot tougher. Tomatoes are a labor intensive industry right now,” Villalobos adds.

Transportation and logistics continue to be a factor to contend with, especially considering freight is up some 30-40 percent from a year ago, says Villalobos. Supply costs on items such as plastic and wood have also jumped. “Commodities worldwide have gone up in price and that puts pressure on our end to provide at the same affordable prices that we’ve been providing,” he says.

Of course, climate change also continues to challenge growers in Mexico. “You get stronger and more frequent hurricanes every year. Even with protected agriculture, your yields come down and your maturing process slows down and in an open field, it makes it also a challenge,” Villalobos says. “Where we’re used to growing tomatoes, we’re used to certain temperatures. Now we’re suddenly getting hard freezes where you didn’t get them before and more rain where you didn’t get them before.”

Bustamante agrees. “When we’re into a rainy season, climate change is making the rain more heavy in shorter periods of time. We also have very high temperatures in areas we didn’t used to have high temperatures and for berries, this is difficult to deal with.”