The COVID-19 pandemic and labour shortages have had a "massive" impact on the already high levels of fruit and vegetable wastage, according to Australia's leading research centre on the issue.

Dr Steve Lapidge is the inaugural CEO of Fight Food Waste Ltd, which incorporates the Fight Food Waste Cooperative Research Centre and Stop Food Waste Australia. He spoke at a webinar hosted by PMA-ANZ, where he explained that fruit and vegetables are by far the most wasted food type.

"There were some interesting trends (from COVID)," Dr Lapidge said. "In terms of the consumer, we saw peaks in food waste after 'panic buying'. People were panic buying vegetables and perishables, and a lot of them went off. So, there was a peak at the start of the lockdown. Then it was quite the opposite, with people trying to make the most of their food so they didn't have to go to the supermarket that often. In the production area, we had increases in crop utilisation; we know Woolworths, for example, were doing whole crop purchases because demand was so high. Right now, it is the labour shortage issue and getting those crops out of the paddock and orchards that is a real mess. How to prevent this in the future is something that we really should be looking at."

Dr Lapidge referenced a report from the Boston Consulting Group in 2018, which found that globally fruits and vegetables are tied with roots and tubers as the highest categories with lost and wasted food, with both recording 46 per cent of total production. However, fruits and vegetables had a much higher volume of 644 million tonnes of losses and wastage compared to roots and tubers at 275 million tonnes.

In 2019, Australia took its first national baseline of food waste and losses that were occurring. It found that Australia currently wastes 7.3 million tonnes per annum.

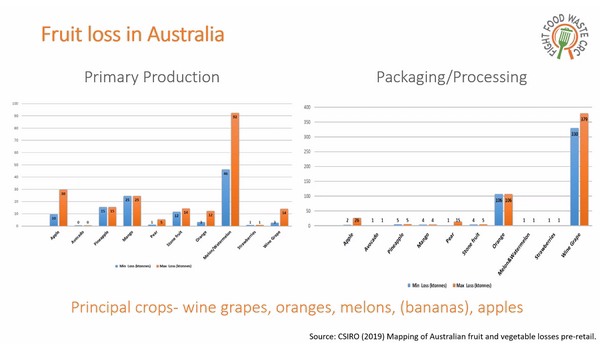

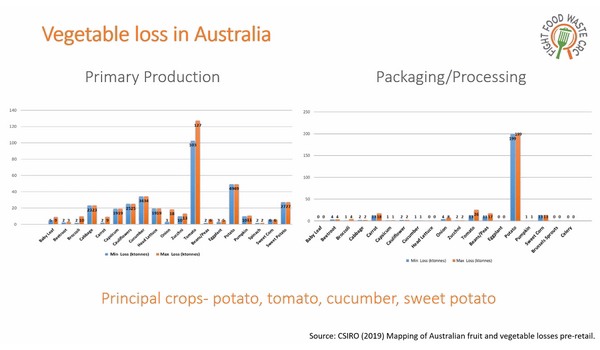

"Another research study from the CSIRO found that out of a production of 6.5 million tonnes of horticulture, around 1.4 million tonnes were lost each year throughout Australia," he said. "That is principally spread between South Australia, Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria.”

Dr Lapidge notes that in 2017, the Australian government committed to halving the country's food waste by 2030, in the release of the Food Waste Strategy.

He differentiates between food loss as occurring before retail and food waste as occurring after purchase by the consumer. Economically, it is a 1.6 trillion-dollar problem globally, and Dr Lapidge says the majority of the volume is lost in primary production, while the majority of value is lost in consumption.

"As food moves throughout the supply chain it creates and gains value," he said. "Unfortunately, when we lose food at the end of the supply chain, we have also used a lot of resources such as water and energy, and costs moving it through the supply chain. So, that is always something that we want to avoid; while we want to avoid losses throughout the supply chain, making sure it doesn't get lost at the end is absolutely critical. However, in the developed world, that's what tends to happen."

Food waste is also unsustainable, according to Dr Lapidge, who points out eight per cent of greenhouse gases come from food that is lost or wasted, and reducing this figure is one of the quickest ways to fight climate change.

"To give perspective, food waste rotting in landfill and releasing methane gasses is 25 times more powerful than Carbon Dioxide (CO2), and it creates six times the amount of greenhouse gasses of the global aviation industry," he said. "It is almost as much as road transport, and in fact, a year like last year (with the COVID-19 pandemic) it probably overtook road transport in terms of the amount of greenhouse gasses generated. So, it is something that we can readily address and will have a massive impact on ensuring a sustainable climate into the future."

He explains that the reasons for the losses differ around the world, from not having the right mechanical harvest techniques to not having the education in the handling stage of the pickers, packers and supply chain workers. While other countries where consumers are responsible for most of the waste, it is due to not having a high enough respect for food.

"It comes down to norms and attitudes," Dr Lapidge said. "It is wasted here because people don't really respect the value of food any more, compared to the past. That is what we need to be addressing longer term. What we need in this country, that has worked well in countries like the Netherlands and other parts of Europe is national behaviour change campaigns that target the social norm around wasting food. We have done it around smoking and skin cancer, we need to do it around food waste as well."

Fight Food Waste Cooperative Research Centre is working on a number of different preventative projects to help reduce waste at different levels. However, Dr Lapidge notes that these differ slightly between the states, and as there is not currently a coordinated national solution at the government level, his organisation ran a campaign last year, mostly through social media, which reached 4.5million people.

"It came at a time where we were going through the COVID lockdown and people were trying to get the most out of their food, so they wouldn't have to go out to the shops as much," he said. "In terms of industry prevention, there is a number of ways we can look at reducing horticulture losses, like improving demand predictions, harvest handling improvements, whole crop utilisation, packaging improvements, improving the cold chain, addressing quality specification and addressing unfair trading practices. In terms of redistribution, we work with most of the food rescue charities and Foodbank is one of our biggest partners and we are working on a number of projects with them."

Dr Lapidge's organisation also sponsored Foodbank's Hunger Report last year that found that out of Australia's population of 25 million, five million people were still food insecure. In addition, despite the high levels of food waste, 65,000 people per month get turned away from food charities.

"Another project we are working on is around tax reform; it is really looking at tax incentives to increase food donation in this country," Dr Lapidge said. "Right now, it is cheaper to throw away the food than it is to donate it. This is something that we are trying to address, in a similar way to the R&D tax incentive, for example. So, there would be an incentive to not only donate but transport and refrigerate food."

For more information

Steve Lapidge

Fight Food Waste CRC

Phone: +61 8 8313 3564

enquiries@fightfoodwastecrc.com.au

www.fightfoodwastecrc.com.au