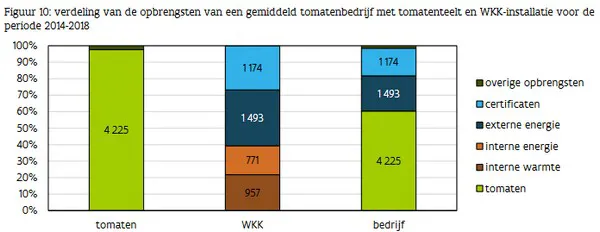

An average Flemish tomato grower with cogeneration for his greenhouse achieves more than one third of his turnover not from the sale of tomatoes, but from cogeneration. Starting point of the cogeneration is that the installation supplies energy to the grower and to help grow profitably.

And that is going well, according to a report of the Flemish government about the tomato cultivation in Flanders. Over the period 2014 - 2018, strong company results were achieved, of which 38% was generated by cogeneration.

Yield from cogeneration

Cogeneration generates energy (heat, electricity, and, not included in the report, CO2) efficiently which is also cheaper that the net. This reduces the grower's variable costs, while cogeneration is also a source of income. At the one hand, growers sell the electricity produced to the electricity net (21% yield) but also trade in the heat obtained - power certificates (17% yield).

These cogeneration certificates are a form of support for the primary energy savings of cogeneration installations compared to separate energy generation, which plays a role in the Flemish energy and climate policy. The investment and maintenance costs of the installation do require significant capital, but the calculation still looks good for growers in Flanders.

Compare

This is a fact growers in the Netherlands are well aware off, and to which they sometimes look at a bit jealously, although the so-called 'market position' is not bad for cogeneration in the Netherlands. The calculations, examples and explanation about how cogeneration is flourishing in Flanders invite a comparison of the costs and yields with those of the southern neighbors.

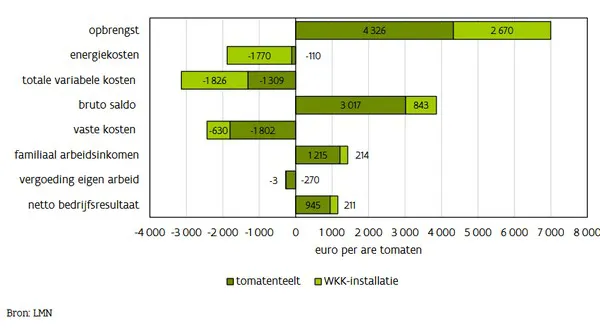

The Flemish report helps with this and gives a bit of insight into the finances of Flemish tomato growers with cogeneration. On average, those growers make up for 3.3 hectare (2.7 hectare in the sample*) over the period 2014-2018, with an average yield of around 2.3 million euro, against around 1.0 million fixed costs and 0.8 million euro variable costs.

It makes cultivation 'very capital intensive', but together with other developments, such as product diversification, the rise of assimilation lighting and year round growing, it is a cultivation which can lead to a 'very good result'. It has to be remarked that there are significant differences per company and per year, inherent to the agricultural and horticultural sector.

View the entire report here. There is also attention for costs from labor and such, which are also worth comparing.

"The report is based on data about tomato companies with a cogeneration installation from the Landbouwmonitoringsnetwerk (LMN) for the period 2014 - 2018. In total, there have been done 77 observations in the period 2014 - 2018, in which company in each year counts as an observation. Companies can be listed multiple years. In the period viewed, 21 unique companies have been filtered out. 16 of them had cogeneration. The sample includes 15.4 companies per year on average. The average area per company is 270 are (1 are is 100 m2). The most of that area has a cogeneration installation: on average 94.3 percent.